Review: ‘The Hidden History of the Smock Frock’ by Alison Toplis

Animal Crossing x Smocks, Museum of English Rural Life

If you do not already follow the Museum of English Rural Life on Twitter (@TheMERL), I would highly recommend it!

Work, Ford Madox Brown, 1852-1865

This painting shows labourers in short white smocks.

Knitted silk smock dress, John Galliano, Spring/Summer 1986

Image via One Of A Kind Archive

Molly Goddard, Autumn/Winter 2019

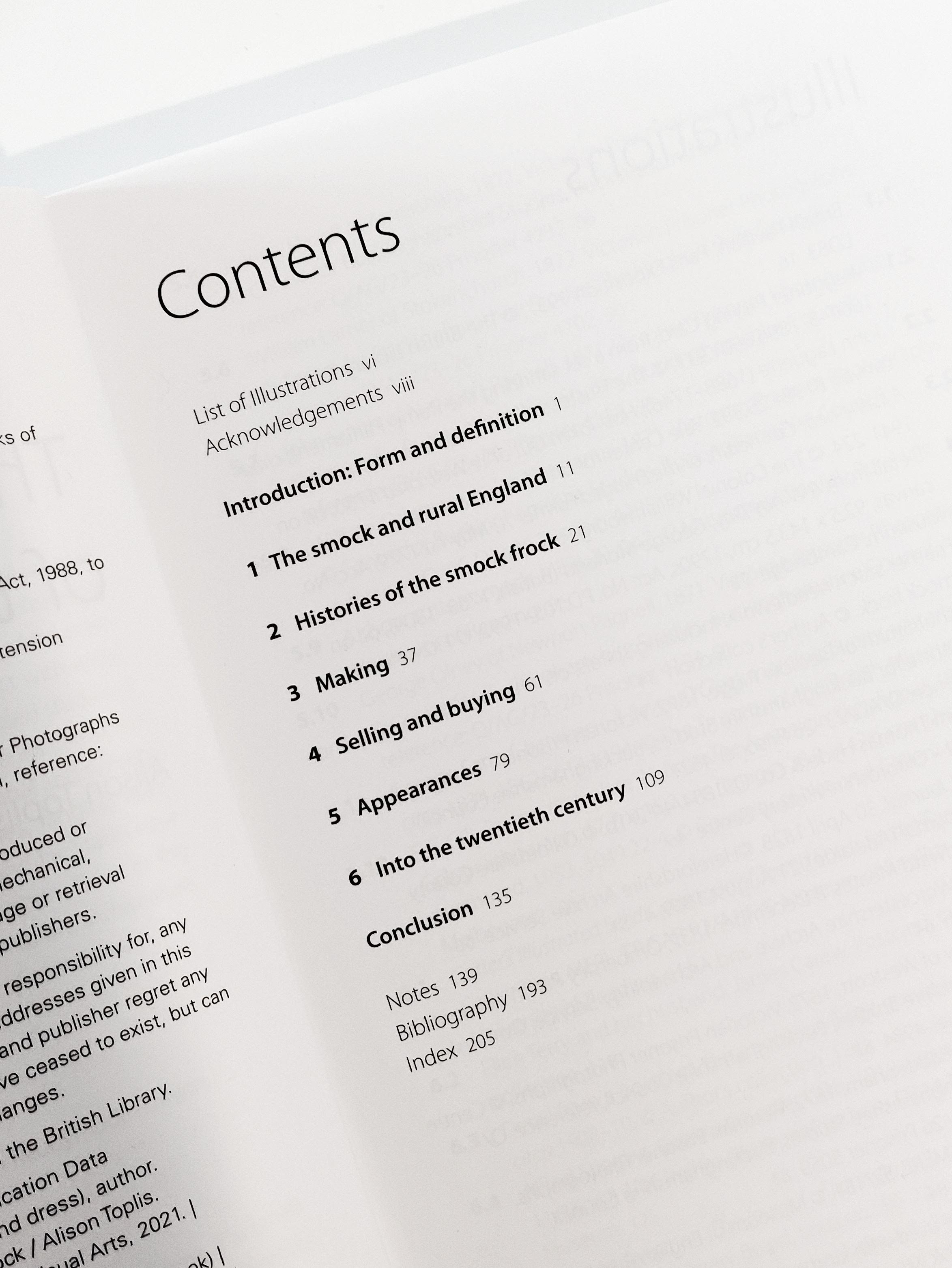

I was fortunate enough to be sent an early copy of Alison Toplis’ new book, The Hidden History of the Smock Frock, by the amazing Rebecca Arnold, who is the series editor for Fashion: Visual & Material Interconnections, published by Bloomsbury in association with The Courtauld Institute of Art. The book is published this Thursday (20th May 2021), with an online launch event on Friday (21st May 2021, which is free to book). I thoroughly enjoyed reading Hidden History this past week and thought it would be fun to review. I was looking forward to a well-researched dive into the smock frock, which is what I got, and indeed this will be an indispensable resource for those studying smocks in the future. But further than that, reading this book got me thinking about a number of different ideas, including how national identity is formed, how collective memory operates, and how much richer clothing practices are than traditional fashion history narratives are often able to communicate.

In all honesty, when I read the words “smock frock” on the cover (which I have to say is really well designed by the way), I had three images in my mind - farmers, painters and sailors. I came to the book knowing nothing, which is always a fun place to start, and I have to say I enjoyed reading it far more than I thought I would. Toplis uses her investigation of the smock to make us reconsider ideas surrounding working-class masculinity and disrupt the dominant fashion history narrative of men’s clothing in the nineteenth century. She traces the origins of the smock from the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, to its widespread usage in the nineteenth century, and through to its decline and revival in the twentieth century and beyond. Using newspaper entries, trade directories, and prisoner photographs, Toplis is able to explore the everyday context of the smock and contextualises it beyond its usual presentation as a quaint object tinted by nostalgia.

The book presents a comprehensive study of the smock, covering the production of the garment, how men acquired them, how men felt about them, how men used them, and also how so many survive today, which is unusual for work clothing. Just in covering this many aspects of a single garment type, it reveals the wider social, cultural and historical context of the smock, which makes for fascinating reading. Rather than trying to define a smock myself, I will quote Toplis: “What makes the smock a smock and not a tunic, blouse or shirt, is the way that the fabric is manipulated and gathered into both the centre back and the front, and on the sleeves, decorative stitching worked to hold the gathers in place forming horizontal bands, the smocking, a later descriptive term for this needlework.” I found it interesting to see just how slippery the nomenclature of the garment is, and was historically, because even in court cases from the nineteenth century clarification appears to have been required.

What struck me most was the complexity of the smock, covering everything from a workwear garment to Sunday’s best. It was offered at different price points for working class men, with the ability to customise them further with buttons and decorative stitching. The first chapter looks at the mythology versus the reality of the garment, seeking to “rescue the smock from the realms of the picturesque”. The “back to land” movement of the 1890s saw the smock imbued with nostalgia and emotional meaning, because rural depopulation saw the garment connected to some sense of idyllic rural childhood. Nostalgia is a strong force in fashion today, but also in terms of how we collectively remember the past, and is something that was fostered by writers and artists at the time where the smock was concerned. Indeed the early 20th century saw the garments being collected for nostalgia purposes and a high number therefore ended up in museum collections.

I am forever fascinated by how museums create and reinforce historical and national narratives, based on the display of what is only ever a fraction of the objects in their collection. A museum display is obviously limited by the objects in their collection, and where historical objects are concerned, this is further limited by what actually survives. That smocks were collected in great numbers allowed them to be present in museum displays today. But you do then have to ask which smocks collectors at the time would have chosen to purchase, and how this can skew our contemporary perspective of them. Which is no doubt why Toplis researched newspaper entries and prisoner photography as a way of looking at smocks in situ (albeit taking into account the fact that the minutiae of sartorial codes are usually lost on us today).

The second chapter provides a detailed overview of the garment while also questioning the standard narrative of English menswear in the nineteenth century. I was interested to learn that flashy clothing remained a part of working class culture, even as plain dark clothes came to be seen as representative of masculine modernity at the time. The idea of the urban dandy cockney makes for fun imagining, and it really does me think about how contemporary fashion will be regarded in the future. There is always a dominant narrative when it comes to fashion history, especially with decade-ism (the 1960s means mini skirts, the 1970s means hippie style, the 1980s means power dressing, etc.), and I do wonder how much history is lost this way. It is understandable that any study or museum display has to be selective in what they choose to focus on, but I really do think that this book helps highlight the importance of studying and recording everyday dress.

The production of smocks is covered in the third chapter, and what struck me most was learning that the majority of smocks were bought ready-made, which for some reason I had not expected. The popularity of smocks is not particularly difficult to understand - they were practical, durable, washable, and versatile, because they could be used to protect good clothes or hide poor clothes. They were also unfitted, which made them easier to produce and sell as ready-made garments. The fourth chapter deals with buying and selling, and it was the purchasing experience that I found especially fascinating to read about. Working class men bought their own clothes, with a visit to the pub followed by the purchasing of a smock apparently a common occurrence. Some shops even catered to late night shoppers, no doubt taking advantage of customers who had had something to drink. It makes for quite a different image of clothes shopping than I had for nineteenth century working class men if I am honest. The chapter also deals with the theft of smocks, which in itself shows the importance the garments held for wearers, because victims were able to identify the wear patterns of their smocks, and took noticeable efforts to reclaim them.

The references to criminality continue into the fifth chapter, especially in relation to prisoner photographs. Photography moved from being a privilege to a form of surveillance and control. Luckily for dress historians, those photographed would show up in their ordinary clothes, providing a wealth of information in terms of everyday dress. The smock in general is also framed as a garment that could conceal identity due to its sheer ubiquity, and was thus used by both criminals and police alike to make identification difficult. However what this also highlights is the minutiae of sartorial codes that were apparent in the wearing of smocks. I do wonder generally about how we address these codes, because they are usually mystifying even to contemporaries unless they are in that social circle already. I think about how we might go about collecting that information today, especially given the number of micro dress cultures that exist. I have often thought about how to approach an ethnographic study of online fashion communities, such as fashion forums, before the information disappears like so much digital clutter. Anyhow, this chapter diversifies the traditional histories of the smock and also situates it within an American and Australian context. Toplis also emphasises the spurious nature of a rural and urban divide, when people moved easily between them and you would see smocks sold and worn in major cities by the working class.

The sixth chapter deals with how the smock moved from a workwear garment to a garment acceptable for women and children, and then its fashionable revival towards the latter decades of the twentieth century. One interesting observation Toplis makes is with regards to the decline in popularity of the smock. Not only did the garment slowly become impractical with an increasingly mechanised workplace, where you could get caught and injured in machinery, but she also notes that the growing proliferation of photography and mirrors may have had an impact on how people regarded themselves, and therefore perhaps the fit of their clothing. The smock did see a resurgence in popularity with the aesthetic dress and rational dress movements, as well as with the elevation of smocking as a craft. But what I found interesting was considering how it entered contemporary fashion, starting with hippie styles in 1960s America and Laura Ashley in the UK. Its entry onto the catwalk was only a matter of time, and indeed smocks appeared in 1970s Yves Saint Laurent and Kenzo collections, 1980s Comme des Garcons and John Galliano collections, and all the way until recent collections from designers such as Molly Goddard.

I really did enjoy reading this, and was surprised at how many different avenues it took me down in terms of thinking about contemporary fashion and dress. I think books like this are important in disrupting and challenging assumed fashion history narratives, allowing us to reframe the way we view everyday clothing from the past. I think this disruption is important not just within a historical context, but it actually has me thinking about how we can record fashion now in a way that truly appreciates the nuances and complexity of what it entails. I can only imagine how many hidden histories are currently unfolding around us.

The Hidden History of the Smock Frock by Alison Toplis is published this Thursday

xxxx